Spearheading innovations to enable new biology

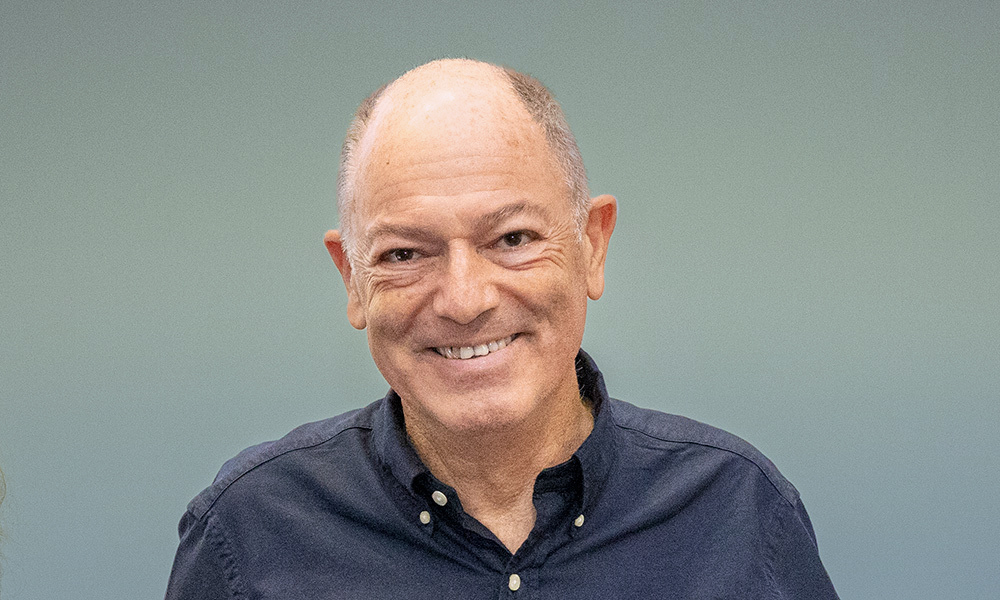

EMBL alumnus and Lennart Philipson Awardee Florent Cipriani reflects on his 30 years at EMBL Grenoble and his multidisciplinary career building technologies that enable new discoveries

Drawn to building and taking apart tools at an early age, Florent Cipriani nurtured his love of understanding how things work and channelled it into a career that spanned structural biology, technology development, and innovation.

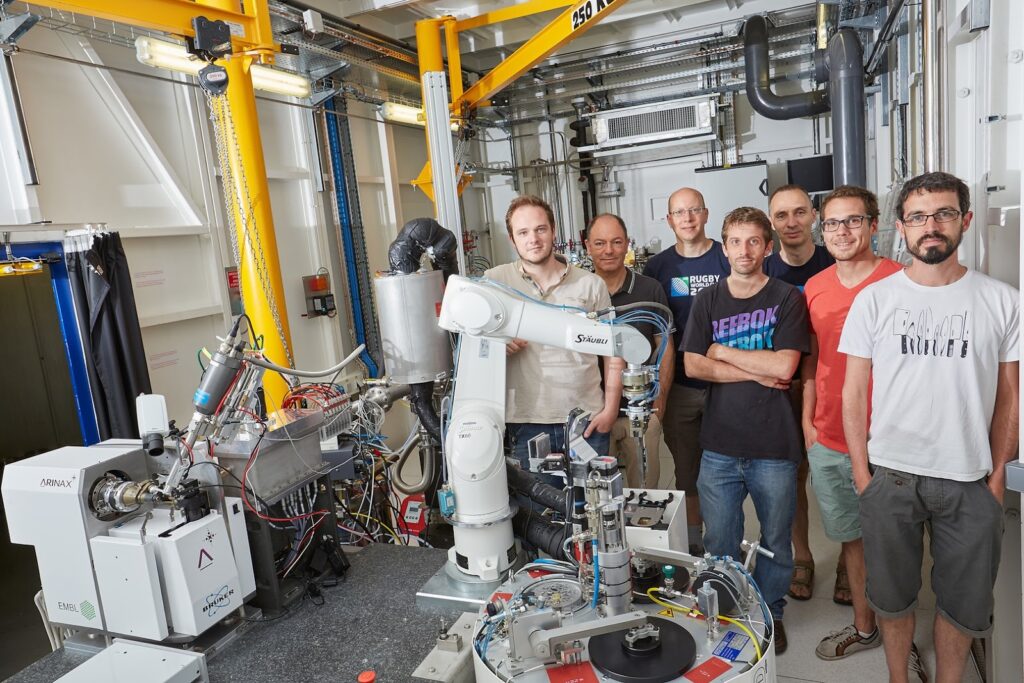

A trained engineer, Cipriani joined EMBL Grenoble in 1991 and went on to lead its Instrumentation Team from 2003 to 2020. During this time, he worked closely with biologists and engineers to design and build innovative technologies that have led to a new era of automation in structural biology research. Some notable examples are micro-diffractometers, robotic sample changers, and the CrystalDirect™ harvester, which automates a critical step in X-ray crystallography.

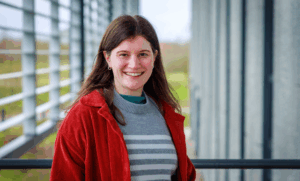

In recognition of his exceptional contributions to structural biology instrumentation, Cipriani was awarded the 2025 Lennart Philipson Award. We recently had the opportunity to learn more about his early inspirations, the process of scientific innovation, and his thoughts on the future of structural biology technologies.

What initially drew you to the field of instrumentation and structural biology, and what motivated you to remain in this area for over 25 years?

I have been told that when I was three, the best way to keep me quiet for hours was to give me a flashlight taken apart into pieces. Which probably says a lot about my interest in electronics and optics! The need to understand how things work is, for me, an incurable disease – though when it comes to humans, I’ve given up trying! Developing an instrument means creating a tool, which is something profoundly human.

As for structural biology, it was really a matter of chance. It started through meeting an exceptional person, André Gabriel at EMBL Grenoble, who was rough on the outside but full of humanity.

Many things have kept me in this field for over 25 years: working in a stimulating environment, tackling technical challenges, seeing users satisfied with my instruments, and contributing to advances in human health, to name a few. But above all, it’s because EMBL is a fair place where everyone has the chance to grow.

Across your long career at EMBL Grenoble, you’ve made over 30 inventions. Which of these innovations are you particularly proud of, and why?

I’m not sure that number is entirely accurate – often, an ‘invention’ is just a smart rearrangement of existing ideas for a new purpose. If innovation is like an iceberg, the invention is the small part you see above the water, and the huge effort to make it work lies underneath.

Still, I’m particularly proud of the ‘on-beam-axis’ camera and the ‘beam display scintillator’ used in micro-diffractometers. This combination allows very precise alignment of tiny crystals with an X-ray beam and has now become a global standard at beamlines. I’m also very proud of the CrystalDirect™ concept, invented together with José Márquez, which led to the world’s first fully automated crystal harvesting system.

How do you approach the challenge of turning a technical solution into an innovation that can be commercialised and used by scientists around the world?

First, the technical solution needs to truly meet a need and arrive at the right time. But what really drives global impact is the scale of the scientific question it helps address. That’s why working closely with excellent scientists on cutting-edge topics is essential, along with having the right support to protect and transfer the innovation to industry. In my case, the environment at EMBL and the support from EMBLEM have been key to making this possible.

Your work has helped automate complex processes in crystallography – from microdiffractometers to CrystalDirect™. What are the most exciting opportunities you see today for automation in structural biology?

Among the structural biology investigation methods I am familiar with, I believe that automating the preparation of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) sample grids is the best opportunity today. Thanks to the pioneering work of Jacques Dubochet and to the ‘resolution revolution’ over the past decade, Cryo-EM has become a method of choice for structural studies. However, the preparation of sample grids remains a major bottleneck, and the lack of reliable quality control methods significantly limits the overall efficiency of cryo-EM platforms. To address this, we launched the EasyGrid project in 2017. Operational prototypes for this are now available at EMBL Grenoble. Still ongoing, the project is currently led by Gergely Papp, my former colleague and successor as Head of the Grenoble Instrumentation Team. I am convinced that this work has a promising future, both scientifically and commercially.

Many of your inventions have helped standardise processes across synchrotron facilities globally. Can you tell us a bit more about this process?

To be processed at MX beamlines, crystals must be mounted on cryo-pins (sample holders). Over the years, many different models have been developed at various facilities, making automated handling either impossible or site-specific. This is why we have initiated the development of the SPINE standard for frozen crystal sample holders, as part of the SPINE European funding program. This was a broad collaborative effort involving most European synchrotrons, as well as consumables manufacturers and distributors. After five years of work and numerous meetings, we successfully published the standard in 2004. We also qualified three companies to manufacture these sample holders and make them available to the scientific community.

Ensuring the availability of reliable consumables was also essential to enable synchrotron users to fully benefit from automation. Beyond automation, the standardisation of consumables has been a key enabler for remote data collection, which allows crystallographers to collect data without travelling to the synchrotron. Users simply ship their frozen samples to any available synchrotron MX beamline. This has also been made possible by the evolution of beamline control interfaces, which have moved from local GUIs to web-based applications.

You’ve worked closely with diverse teams and industrial partners over the years. What have been the key ingredients for successful collaboration in your experience?

In my experience, the most important ingredient for a successful collaboration is to establish a relationship based on fairness, openness, and sincerity. It is essential to always consider the interests of the other party as seriously as you would your own. This mutual respect and shared sense of purpose are what build trust and allow both sides to work towards common goals effectively.

Looking back on your time at EMBL, what advice would you offer to the next generation of innovators working behind the scenes?

As I’ve already mentioned, EMBL is an incredibly stimulating environment where everyone can grow. It provided me with freedom in choosing my projects and actions, trust – even when projects stalled – and access to the resources needed to bring those projects to success.

There is no universal recipe for innovation. It depends on the field and on personal experience. In my view, when starting a project, spending too much time looking at what others have done or are doing can inhibit your creativity. First, you should reflect independently, relying on your own expertise and ideas. The best innovations often come from completely unrelated fields – this is particularly true in instrumentation. And once you believe you are in the right direction, stay focused and committed, even if competitors seem close to achieving the same goal. In the end, the best solution will prevail.

What does receiving the Lennart Philipson Award mean to you, both personally and professionally?

For me, this award gives extraordinary value to the years I have spent working alongside my team to support scientists in addressing their most challenging questions. It serves as a strong reminder that behind every scientific breakthrough, there are good instruments – and that technical innovation is essential for scientific progress. Shining a light on instrumentation is particularly important within a research institute like EMBL, where technical achievements are sometimes hidden within scientific publications. Improving the visibility of this work not only acknowledges the vital role of engineers and technicians but also helps attract new talent to this essential field.