Alvis Brazma: what I’ve learned

EMBL-EBI alumnus Alvis Brazma reflects on how mathematics and mountaineering have shaped his life and why keeping things simple in bioinformatics is key

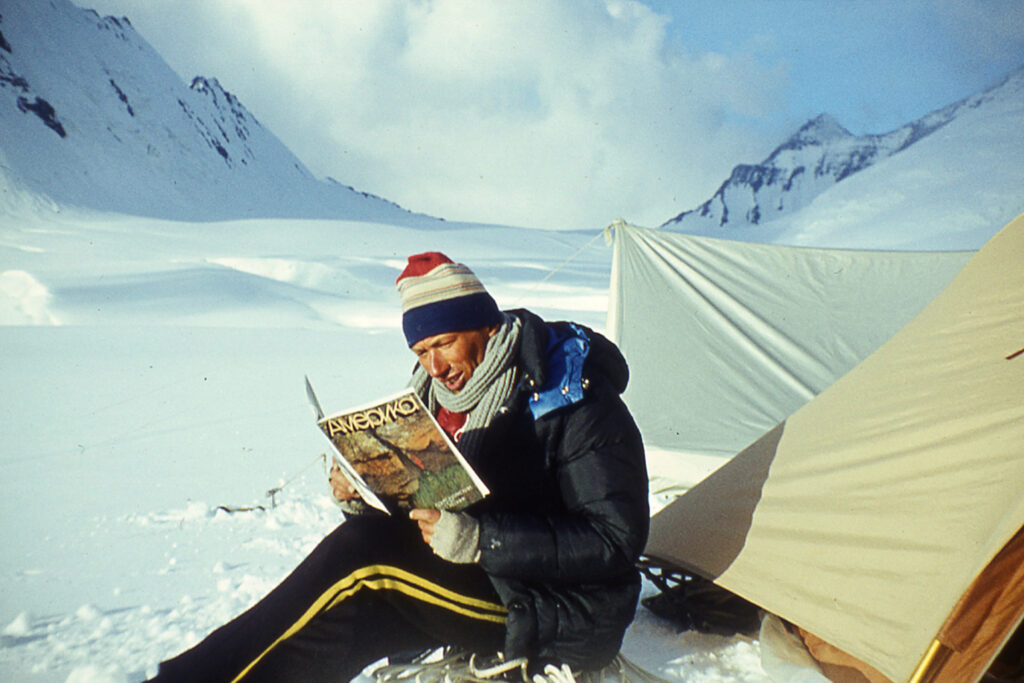

Alvis Brazma has climbed some of the world’s highest mountains, but the irony that he’s spent most of his career in the flattest part of the UK – Cambridgeshire – is not lost on him. “I traded real mountains for mountains of data,” Brazma jokes as we embark on a whistlestop tour of his scientific career, including almost 30 years at EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI).

As one of EMBL-EBI’s longest-standing members of staff, Brazma has seen the institute grow and transform. He’s witnessed bioinformatics change from a fringe science into a necessary foundation for biological discovery. Brazma himself instigated the development of some of EMBL-EBI’s most well-used data resources and lobbied fiercely for making scientific data open and accessible to all.

“Alvis has been a great source of inspiration and amazing fun to work with. He helped launch my career, showing me a pathway to success and when I got lost, he gave me the map.”

“Alvis has been a great source of inspiration and amazing fun to work with. He helped launch my career, showing me a pathway to success and when I got lost, he gave me the map.”

Originally from Latvia, Brazma is a mathematician by training and has always been fascinated by how maths can help us understand life. “When I was growing up, Latvia was still part of the Soviet Union, so my childhood, career choices, and worldview at the time were somewhat shaped by that reality,” he said.

In the Soviet Union, academia was one of the few options that enabled someone to have a career without joining the Communist Party. It also meant he could work with world-renowned mathematicians. Brazma studied Applied Mathematics at the University of Latvia and wrote his thesis under Professor Jānis Barzdiņš, who had been a postdoc of the great Soviet mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov. Kolmogorov’s axiomatic approach to science, which centred on looking for the basic principles through which you can explain everything, resonated with Brazma. “This is very different from how biology traditionally worked, because biologists were typically interested in the exceptions rather than the rules,” he mused.

To defend his PhD thesis, Brazma often had to travel from Riga to Moscow. “I still remember bringing back bananas, lemons, and oranges, which were unavailable in Latvia.” These were also the years when Brazma, an avid mountaineer and endurance runner, explored the expanse of Central Asia and the Caucasus.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, travel restrictions for countries in the USSR became less strict. With the help of Latvian diaspora members, Brazma got a position at New Mexico State University. In its library, he came across the first articles about the Human Genome Project and the plans to establish the European Bioinformatics Institute.

What followed was a return to the now-independent Latvia, which was still going through a transition period. Brazma was torn between wanting to be part of rebuilding the country and desiring to work at the forefront of science. It was a difficult choice, which he made gradually.

He accepted a visiting scientist position at the University of Helsinki, working with Esko Ukkonen, a leading Finnish computer scientist known for his contributions to string algorithms and suffix trees, widely used in fast searches. In 1996, Brazma published his first bioinformatics paper. Other researchers were working on discovering patterns in DNA sequences, so to get an edge, he and his colleagues started looking at non-coding sequences, which he suspected would become increasingly available as the first full genomes started to emerge.

“This is also around the time I met Tom Flores, a newly recruited Team Leader at EMBL-EBI,” remembered Brazma. “Tom gave a seminar at the University of Helsinki, and I had tons of questions. I wanted to understand why I couldn’t get what I needed from EMBL-EBI data resources. The discussion ended with Tom telling me to come to EMBL-EBI to sort it out myself. This is how I ended up there.”

In the 1990s, the microarray revolution started making waves in the life sciences. Microarrays became a key experimental tool, enabling the analysis of genome-wide patterns of gene expression for the first time. “The private sector in particular was racing to leverage this new data type, so my first role at EMBL-EBI was to make this a reality for the institute’s newly formed Industry Programme,” Brazma said.

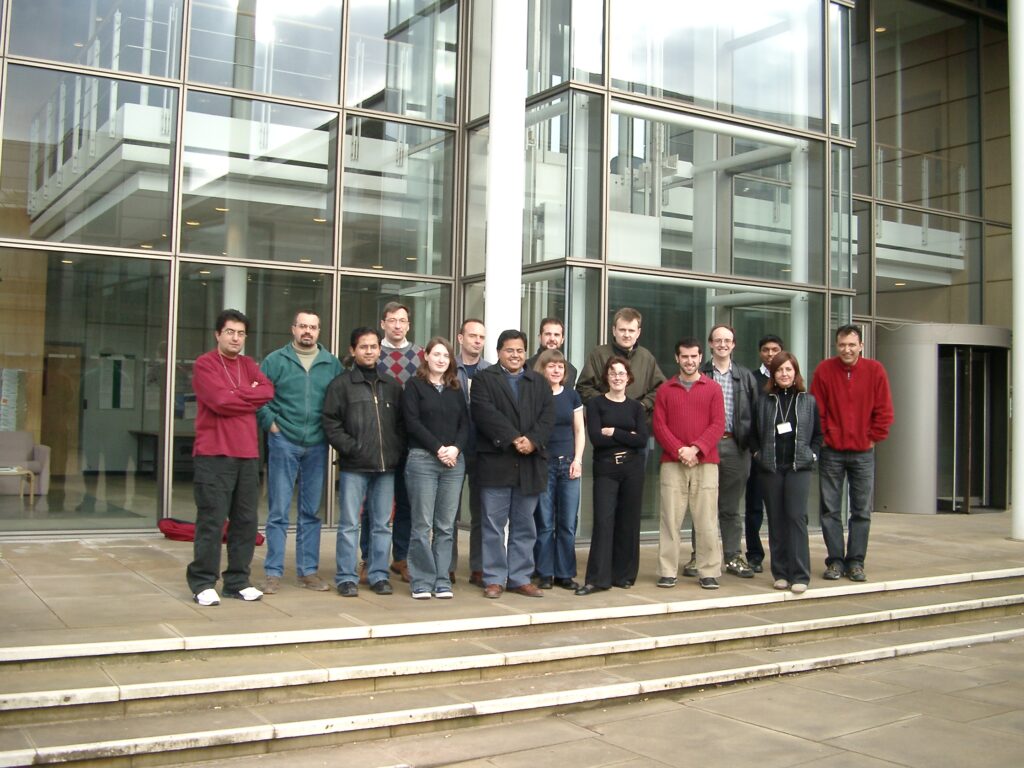

Brazma became a Team Leader with the support of Graham Cameron and Michael Ashburner, the first co-Directors of EMBL-EBI, and Fotis Kafatos, EMBL’s Director General at the time. Brazma also hired his first team member: Jaak Vilo, whom he knew from Helsinki and who later became Head of the Institute of Computer Science at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

“A significant achievement was establishing the community-driven MIAME and MAGE standards for microarray gene expression data. This could not have been accomplished without Alvis’s dedication to tirelessly learning and documenting the fundamental aspects of biology.”

At EMBL-EBI, Brazma and his team developed the first data resource to record microarray data and metadata: ArrayExpress. This is still available through EMBL-EBI’s BioStudies database. Brazma was also the instigator of the MIAME data standard, which he used to lobby researchers to make their microarray data public and available for reuse. The principles of MIAME echo through most subsequent data standards and the widely-used concept of FAIR – making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable.

Over the years, microarray technology began to be superseded by deep genome sequencing. Functional genomics grew as a discipline. Brazma’s team increased in size and developed other data resources for functional genomics. In 2013, they set up the Expression Atlas, offering scientists a powerful way to find information about gene and protein expression in all species. They also launched a sister resource called the Single-Cell Expression Atlas in 2018, creating a home for data from top-of-the-range single-cell RNA sequencing technologies. Brazma was also one of the founders of the BioImage Archive, EMBL-EBI’s data resource for bioimaging data.

In parallel with his data resources team, Brazma also led a research group. In total, he’s had 12 PhD students, all successfully graduated, and many postdoctoral fellows.

Brazma’s vision and contributions go far beyond science. He played an essential role in bringing Latvia into the EMBL fold as its 29th member state. “To me, the key benefit of being an EMBL member state is the access to an incredible network of contacts, state-of-the-art facilities, and scientific expertise,” he explained. “Countries can leverage this ecosystem to empower their communities and also apply for funding that would otherwise be out of reach.”

More recently, Brazma, who has always been an avid reader of both scientific literature and popular science, has achieved what many only dream of. He compiled years of research and work into an insightful popular science book linking information and biology. The volume, called Living computers, recently published by Oxford University Press, looks to understand life and evolution through the lens of information processing and computing. As always, Brazma’s timing couldn’t be better, with generative AIs such as ChatGPT exploding into the mainstream.

“This is a great book – Alvis brings out the correspondences between von Neumann universal replicator and the associated computer science theory and molecular biology. One of the most thought-provoking books I’ve read in a long time!”

Following his official retirement from EMBL, Brazma was granted the status of EMBL Visitor Emeritus, meaning he will continue to represent the organisation and participate in EMBL life when time allows it. The first thing after his retirement was to teach at the Ukrainian Biological data science summer school, a rare opportunity that brings the community together.

Below are a few of Brazma’s reflections on his life and career as he approaches his retirement from EMBL. He also kindly shared some of the lessons he’s gleaned over the years.

The early years

I’ve loved science ever since I can remember. My father, who was also a mathematician, died when I was seven. By this time, he had already passed on to me his love of numbers. I still remember all the popular science books and almanacs scattered around the house when I was little. I always knew I would be a scientist, there was no other option, really.

One of my early memories is listening to my parents play music together. My mother, who was a pharmacist, was also an amateur opera singer. She would sing while my father would play the piano.

At school, I discovered I was good at long-distance running. I’ve run seven marathons in my life. And since I enjoyed endurance sports, I also did a lot of mountain climbing. Twice, I made it higher than 7,000 metres, in the Pamir mountains, in Tajikistan. There is something transcendent about climbing; it pushes you to the edge of your physical limits, and after all that, it rewards you with the bigger picture.

There are times of great learning that don’t have to be scientific. Moving to the United States after the fall of the Berlin Wall opened my mind to how things worked in the West. And while it didn’t result in any major scientific revelations, it was like seeing the world with new eyes, and it felt incredibly invigorating.

Microarray revolution

Microarrays were the hot new thing in the 1990s, and I really wanted to give EMBL an edge in this new field. The experiments were expensive at the time, so being at EMBL-EBI, I thought maybe we could build a database, collect all microarray data from around the world, and make them available to everyone. And that’s exactly what we did.

I deeply believe that microarrays started functional genomics as a discipline. Sequencing captures the ‘anatomy’ of a genome, while microarrays look at physiology. For the first time, microarrays allowed us to see what was happening functionally – what the genes were actually doing.

Community buy-in was key. We wanted to encourage people to share their microarray data in our ArrayExpress data resource. So we founded the Microarray Gene Expression Data Society, which was hugely influential in convincing scientists to properly describe and share their datasets. We had around 200 members, which was huge in those days, because the community was so small.

Keep it simple – this is the main lesson I’ve learned. We made mistakes along the way and almost all of them came from overcomplicating things. I wish someone had sat me down and told me this 25 years ago. We were overambitious, and this made things harder than they needed to be. When it comes to bioinformatics and data standards, the key is to start simple. It’s great to see new resources, such as the BioImage Archive, getting it right.

On science and leadership

Leadership makes a huge difference. I’ve been lucky to work with some brilliant scientific leaders, for example, Fotis Kafatos, EMBL’s Director General (DG) between 1993 and 2005. High throughput and computational biology were still in their infancy at the time, but Fotis Kafatos understood their coming importance and was instrumental in establishing functional genomics at EMBL.

Have empathy for your colleagues and team members. Without this, you won’t get far. Working with Dame Janet Thornton, Director of EMBL-EBI between 2001 and 2015, really drove this point home to me. Janet is unique because she is at once a strong leader, an inspiration, and an incredibly nice person.

Honesty has to be at the heart of the scientific process. As a scientist, you have to scrutinise your results and go the extra mile when verifying things. If your result turns out to be an artefact, it can be disheartening, but you will have done the right thing by double-checking.

For young scientists, my advice is to follow your star. Do what is exciting to you. Look for an edge and try to be in a field that is just beginning. My star was bioinformatics. If I was just starting off now, I would perhaps be looking for a niche in AI.

Writing my book, I think I finally understood what life is. I’m not sure everyone will agree, but it has helped me achieve peace that I finally understand what it’s all about. To me, the defining feature of life is the ability to record and process information. And if you have this and combine it with physics, then you get living organisms.

I made some of my happiest memories exploring the world, both at the molecular level and at a bigger scale. Whether analysing data, discussing with colleagues, or cycling over the Himalayas, I’ve always tried to make the most of the moment. I’ve been incredibly lucky in many ways in my life.