Welcome: Florian Wollweber

The new group leader will explore the origin of eukaryotes and their complex cellular organisation by studying Asgard archaea and other non-model microorganisms

After completing a PhD in Germany and postdoctoral research at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, Florian Wollweber has joined EMBL Grenoble, where he will explore the origin of eukaryotic cells and their membrane-bound organelles using multi-scale imaging and structural cell biology approaches.

At EMBL Grenoble, Wollweber’s group will combine advanced imaging techniques – such as cryo-electron tomography (cryoET), expansion microscopy (ExM), and super-resolution light microscopy – to investigate fundamental questions in evolutionary biology, with a particular focus on the origin of eukaryotes and cellular complexity. A central theme of his work is to understand the cell biology of Asgard archaea, a group of microbes closely related to the ancestors of eukaryotes.

Can you explain what your group will do?

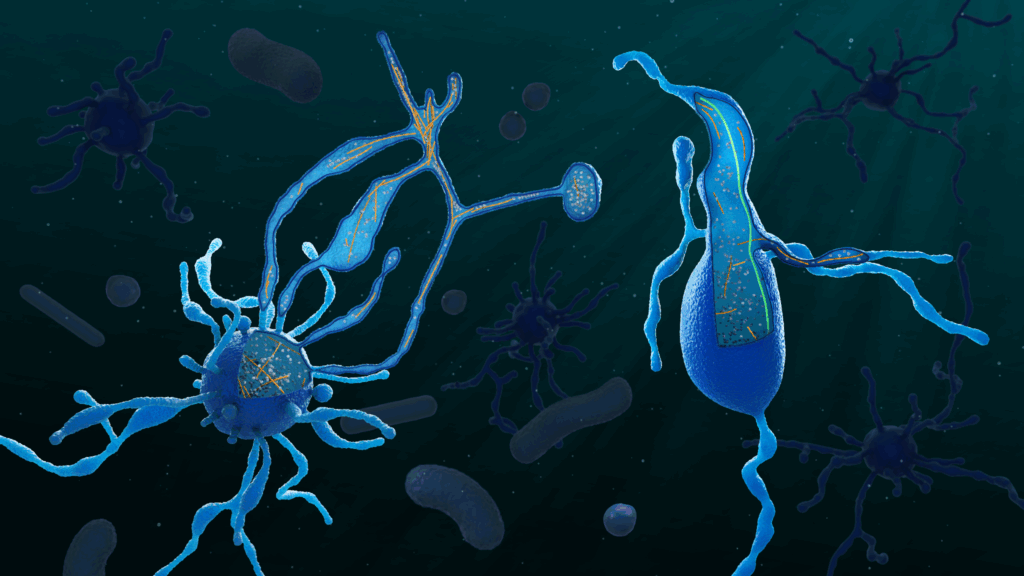

We are trying to understand one of the biggest mysteries in biology, the origin of eukaryotes. This is a particularly difficult question to address. Eukaryotic cells originate from a merger of at least two different cells: a bacterium that later became the mitochondrion and an archaeal host cell. This event likely happened only once, about two billion years ago. The closest living relatives of this archaeon, called Asgard archaea, were only discovered recently. Their cell biology must be incredibly exciting, because their genomes encode a large number of proteins that one can typically only find in eukaryotes. This could, of course, suggest that these cells are already somewhat complex – but we don’t really know much yet. The problem is that they are extremely difficult to work with: they grow very slowly, sometimes taking weeks or months to divide, and are challenging to maintain in the lab.

We use a combination of different imaging techniques to study these cells, such as cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET), expansion microscopy, and other (super-resolution) light microscopy modalities. Even though these samples are exceptionally challenging to visualise, these imaging tools have already allowed us to discover that these archaea have a complex cell architecture with protrusions and, similar to eukaryotes, an actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. We now want to mechanistically study their cell biology to reconstruct what the eukaryotic ancestor might have looked like. In parallel, we will also apply our imaging approaches to a number of non-model eukaryotes to address related questions in evolutionary cell biology – for example, how an endosymbiont might become a fully integrated organelle. In both cases, one of our long-term goals is to develop tools to image cells directly from environmental samples, simply because most organisms cannot be grown in the lab (and amazingly, EMBL is already moving in this direction with initiatives like the TREC expedition!).

You combine cell biology and structural biology in unusual ways in your work. What inspired you to bridge these disciplines?

Cryo-ET is an amazing technique precisely because it bridges these two disciplines: we can simultaneously visualise cellular ultrastructure (nowadays even in very complex systems, such as tissues) and do in situ structural biology – this means, in an ideal case, we can look at protein structures within their native cellular environment. This is obviously a very useful resolution range to bridge within the same sample. Importantly for us, we do not depend on genetics, so we can study cell biological mechanisms even in non-model organisms, which constitute most of life on Earth. At the same time, cryo-ET still has its limitations, both in resolution and throughput. While it’s a great discovery tool that allows us to ‘just look’ at biology, it is still relatively low-throughput and not always ideal for quantitative analyses.

Because of this, we typically combine cryo-ET with complementary imaging modalities and structural biology techniques, such as single-particle cryo-EM and expansion microscopy. I am particularly excited about expansion microscopy, which has already allowed us to study the cell architecture of Asgards and localise some of their eukaryote-like cytoskeletal proteins. It seems to work for almost every sample and has sufficient throughput to capture even rare cellular events.

How do you see cryo-ET evolving in the next few years?

For evolutionary cell biology in particular, we will have to understand the cell biology of organisms that we cannot grow in the lab. Cryo-ET has enormous potential here, but it is also an incredibly complex, expensive, and often frustrating workflow. All too often, one of the many steps fails – and even the first step (freezing the sample) can be a real challenge. Increased automation at every stage (including sample preparation, such as EasyGrid developed at EMBL Grenoble) will make cryo-ET more robust and accessible. This would allow us to focus more on biology and less on troubleshooting. At the same time, we will have to find better ways to extract quantitative information from these very information-rich datasets and to combine cryo-ET with other imaging and omics techniques, ideally applied to the same sample.

What advice do you give to young scientists who want to cross disciplines as you do?

I would encourage them to reconsider why they want to do science at every new step of their career, and not to be afraid to switch fields if their curiosity takes them elsewhere. I started out studying biomedical sciences as an undergraduate, then focused on mitochondrial ultrastructure during my PhD. Driven by a fascination with their endosymbiotic origin, this eventually led me to study the origin of eukaryotes in strange archaea and protists. Switching fields is not easy, but it can definitely be one of the most exciting aspects of being a scientist!

Can you tell us about some of your hobbies and interests?

I love skiing and running in the mountains, so I feel incredibly lucky to have moved to the only EMBL site located right in the Alps. I haven’t had much time yet to explore Grenoble’s trails, but the view from the lab alone is already pretty amazing!