Flashback Friday: Who is Leo Szilárd?

EMBL celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2024, and in so doing, we’re digging through the archives for some fascinating stories from EMBL’s past publications to republish in this blog.

The following is an EMBLetc. article from the first issue of the publication in July 1999 about the eponym of EMBL’s library, who would have been 126 years old on 11 February this year.

Leo Szilárd was born in Budapest in 1898. He began his career in science in 1922 as a physicist at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at Berlin University and then moved to the medical college at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. While there, he collaborated with T.A. Chalmers and was one of the first scientists to envisage the possibilities of nuclear fission and chain reactions.

In 1937, he left England to take up a post at Columbia University in New York. During the 1930s, he advised scientists not to publish results of chain reaction research, fearing the misuse of its dangerous possibilities. But equally aware of the danger at that time of Nazi Germany developing an atomic bomb first, he pressed the US government to support nuclear research and in 1939, helped persuade Albert Einstein to write to President Roosevelt advocating the immediate development of the atomic bomb. Thus, Leo Szilárd became one of the key scientists involved in the Manhattan Project. Although Szilárd had succeeded in helping to create the nuclear bomb, he failed in his passionate attempts to restrain its use. After Hiroshima, he worked intensely to advocate the peaceful applications of atomic energy and the international control of nuclear weapons.

In 1946, Szilárd’s scientific priorities shifted from physics to biology. Jacques Monod explained the move in this way: “…because of its very complexity and uncertainties, biology needed ideas, many ideas to be discussed, tested, rejected, or temporarily accepted, that is, precisely the kind of goods that he knew he could provide in abundance and enjoyed dealing with.” One of these abundant ideas was that a European laboratory for molecular biology should be established.

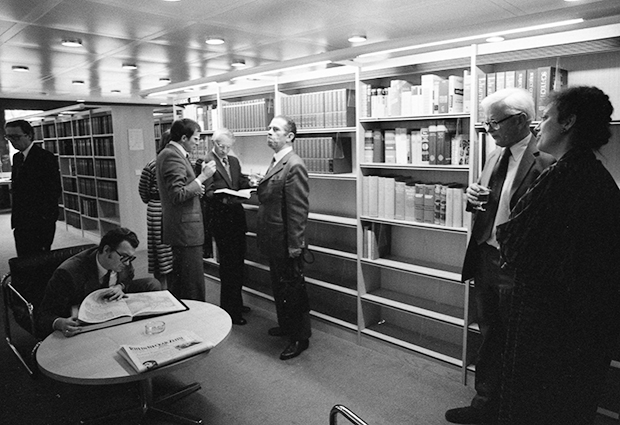

“The Szilárd Library started off with a table, a chair, and a cupboard in the DKFZ in October 1974. Thirty journals were ordered and when the cupboard was full, everything was moved, with a few scientists, to the ‘Alte Biochemie’, Bunsen’s old laboratory. At the end of 1974, we took possession of the Library on the hill. Then it was rather empty, now it is nearly full…In 1978 with some trepidation, we tried our hands at online searching. We used a telephone and a teletype machine, which spat out metres of light-sensitive paper at us…if we managed to contact the database!”

In the autumn of 1962, Szilárd met with Victor Weisskopf and Italian physicist Gilberto Bernardini to discuss the laboratory. They then got in touch with a number of molecular biologists, including Sir John Kendrew, Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, and James Watson, all of whom showed interest. Slowly the idea began to take shape and in August of 1963, a meeting was held in Ravello, Italy, which resulted in three main proposals: that the project should be European and not worldwide; that in addition to a laboratory, fellowships and advanced teaching courses should be provided; and that a formal body known as the European Molecular Biology Organisation (EMBO) should be established.

Szilárd died in California in 1964. He was a scientist who was deeply concerned with world peace and with efforts to create what he called “a more livable world.” In 1962, he founded the Council for a Livable World whose symbol is a dolphin; this same dolphin motif is incorporated in the EMBL library book-plates as a reminder of this aspect of his life’s work.

This article was originally published in EMBLetc., issue 1, July 1999. Find more stories related to EMBL’s Szilárd Library here.