Open Access Week 2025, Day 4: All things copyright

By Katherine Hughes, EMBL Open Science Information Specialist

Welcome to Day 4 of The 5 Days of Open Access Week!

For Open Access Week 2025, OSIM will release a blog post each day on a different topic with a short quiz or activity. Complete each activity, and you will be entered in a raffle to win a prize. You have until Friday 24th October to complete all activities.

With this year’s theme being ‘who owns our knowledge?’ it is important for authors to be informed about copyright and their rights. It is also important to acknowledge that by picking a more restrictive license, it can limit the impact of your work and the ability for scientists like those at EMBL to use that work in their research.

EMBL has a strong commitment to open science. The first open access policy was established 10 years ago in 2015 and has evolved into our current Open Science Policy that includes research articles, data, and software. EMBL-EBI hosts some of the most comprehensive open data services in the life sciences, such as the European Nucleotide Archive, UniProt, and the literature database Europe PMC.

Projects like Open Targets and PRIDE rely heavily on open access articles published under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Papers published under a more restrictive license such as CC BY-NC-ND, are not included in these databases because of their restrictions on reuse.

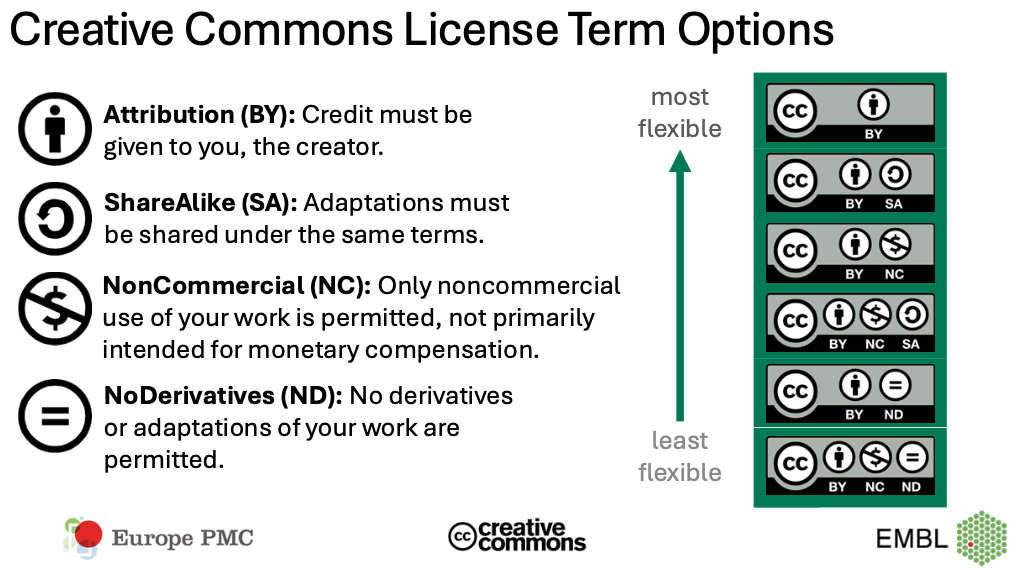

Creative Commons licenses allow authors to decide what users can and cannot do with their published work. The most flexible license, and the one mandated by most funders and research institutions is the CC BY license which requires attribution be given to the author. A work posted under a CC BY license can be copied and redistributed for instance if a teacher wanted to provide reading in a classroom. The work can also be adapted by remixing or building upon the original work, for example works can be translated into another language. On the other end of the spectrum, there is the most restrictive license, the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No-Derivative (CC BY-NC-ND) license. With the increase of AI scraping of academic repositories, there has been an increase in more work being published under CC BY-NC-ND).

This is a worrying trend and one that is unlikely to protect authors from AI. As discussed in yesterday’s post, when an author’s paper is accepted, they are required to sign a Copyright Transfer Agreement (CTA). The CTA gives the publishers the right to publish and disseminate an author’s work on their platform and via other means. However, a CTA generally goes one step further than necessary and transfers the copyright to the publisher. While the authors retain the moral copyright of the work, which provides them with the right to be identified as the author, they give away their economic rights to the paper which include the right to copy, lend, or receive remuneration.

Now, not getting paid wouldn’t normally be a big deal. Academic authors are rarely paid for their papers (usually they must pay to get published). The publishers don’t need to own the copyright to a work to publish it, they need a license to publish it. Many authors may decide to select the CC BY-NC-ND license under the misunderstanding that by selecting the NC and ND licenses, they would have the right to decide if their work would be used commercially. Unfortunately, much like if an article is published behind a paywall, when an author signs a CTA, the publisher ensures that the commercial rights are transferred to them. This means that if an author wants to reuse a figure for a future publication, they will need permission and have to pay the publisher to reuse their own work.

Moreover, this allows publishers to sign deals with AI companies. Several publishers have already made deals with AI companies worth millions with little or no compensation going to the original authors. Picking a more restrictive license only increases the already large profit margins of publishers.

Finally, while things are still uncertain, recent court decisions make it increasingly unclear whether a more restrictive license would protect your work from being used to train AI. Under the US Fair Use policy, AI is seen as transformative and therefore would not be copyright protected. Creative Commons licenses are copyright licenses. Even the most flexible license, CC BY requires AI companies to give attribution to authors.

What is apparent is that publishing under restrictive copyright licenses would slow the progress of science. Science is built upon the previous work of others and by putting research back behind a paywall it hampers public access and excludes a majority of the world’s researchers. During the COVID pandemic, publishers allowed works to be free to read on their platform expressly to speed up the response to the public health crisis. Placing work under a more restrictive license would undo the progress that has been achieved in the last 20 years of the open access movement.

Complete the quiz to test your knowledge of open access (and for a chance to win a prize).