Read the latest Issue

Ken Holmes, one of the visionaries behind the establishment of EMBL and the EMBL Hamburg outstation, looks back to where it all began.

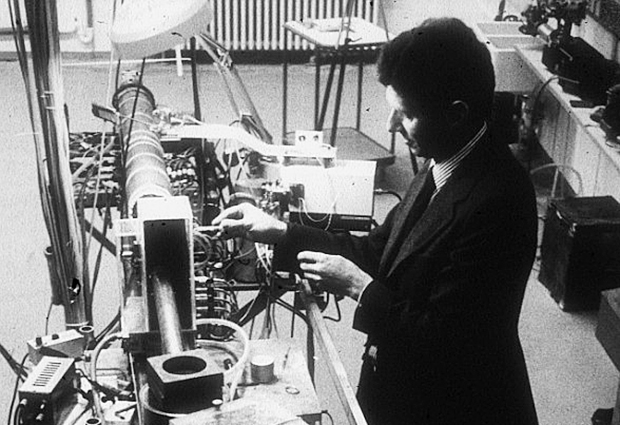

In the late 1960s, as Director of the Department of Biophysics at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, I was part of a group of scientists utilising X-ray diffraction as a means of studying the physiology of muscle. In principle, X-ray diffraction from contracting muscle fibres could tell us how the component molecules were moving but, until I came across the work of the Nobel Prize Winner Julius Schwinger on the theory of synchrotron radiation, we lacked enough X-ray intensity. Our subsequent search for ‘rings of electrons’ led us to the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg. Together with Gerd Rosenbaum, who had fortunately joined me as a doctoral student, we set up equipment that enabled us to use this beam to get a diffraction pattern from a muscle specimen – achieving a ten-fold gain in intensity, high optical quality, and we are still witnessing its open-ended potential today.

The work redefined the aims of the future EMBL. At a meeting of the steering committee in Konstanz in 1969, there was a consensus that EMBL should specialise in large projects that could not be undertaken by national labs, such as synchrotron radiation. This resulted in an EMBL outstation in Hamburg, set up by Gerd and I – we built the world’s first ever X-ray beamline at DESY, before EMBL officially existed. Today, alongside recombinant DNA technology, the technique is one of the twin pillars of molecular biology.

Today, alongside recombinant DNA technology, the technique is one of the twin pillars of molecular biology.

I did my PhD on the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) at Birkbeck College London with Rosalind Franklin. Very sadly, she died of cancer before I had finished. I completed my doctorate with Aaron Klug, with whom I spent the next decade and more working out the atomic structure of TMV. This is a fibre diffraction problem and involves lots of Bessel functions. From this work I gained the expertise that enabled me to calculate the expected intensities of synchrotron radiation from Schwinger’s complex formula and later apply methods I learned to solve the structure of actin.

Coming to Heidelberg in 1968 was something of an adventure. From an initiative originating in part from my young department at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Heidelberg was offered as a site for EMBL. Founding director John Kendrew, a personal friend and colleague at the Laboratory for Molecular Biology in Cambridge, asked my wife Mary to set up the Szilárd Library. I also joined Heidelberg’s rowing club – probably more valuable than many years of health insurance. Now we’ve settled in the Mühltal in Handschuhsheim. Meanwhile, EMBL has gone beyond just large science. Most important, it offers a unique venue where young scientists from all over can come to do excellent research and meet to form friendships and collaborations that are truly pan-European.

Looking for past print editions of EMBLetc.? Browse our archive, going back 20 years.

EMBLetc. archive